To read the Best Australian Films of 2025, subscribe to our newsletter on the free or paid tier here.

Paid members go in the running to win a physical copy of the number one film on the list.

This article contains some basic footnotes. I recommend reading the post in order instead of jumping to them right away.

I didn’t sleep very well in 2025.

There’s a few reasons why[1], but the one that’s most pertinent to this list has been the growing concern I’ve been feeling over the current state of the Australian film industry.

Yes, I do stir at night as I dream about the state of Australian cinema. I dream about the quality of the films being produced. I have dreams where a game of 'Australian film or tourist ad?' plays (I have a fairly good score, but alas, I do get tripped up between the two sometimes). I dream about the domestic and international reception of Aussie films.

For a rundown on the international reception of Australian films, read Antony I. Ginnane report on FilmInk here and for the domestic reception, become a member of IF.com.au which regularly reports on box office takes. An early draft of this intro outlined the highs and lows of state and federal funding for Australian films, and while I’m not going to dive into that here, I do encourage you to dig into Variety’s digestion of the 24/25 Screen Australia Drama Report[2] right here.

On a box office level, it wasn’t the best year for Australian cinema with Kangaroo comfortably topping the local box office, and only a handful of other titles managing to get over $1m domestically (Bring Her Back, The Correspondent, Together, Spit, The Travellers, and the holdover of Better Man's box office continued from 2024 to 25). At time of writing, the full box office total for 2025 isn't available, but keep an eye out for another annual 'death of Australian cinema' article to appear when it is published.

On a creative level, there were some highs, mostly mid-range fare, and a smattering of lows, with some genuine classics being minted and nothing egregious enough to warrant being called 'the worst thing since The Naked Wanderer[3]'. (Although, if we consider Anaconda an Australian film (it's not) because it was shot in Queensland, then that quite easily takes the cake as being as worse a reason to have a paid trip to the Gold Coast as anything else I've seen shot in that state.)

Independent filmmaking is increasing across the nation giving way to a new movement of Australian storytellers working to tell stories about their Australia. I've been calling this group of filmmakers ‘the rising swell of Australian cinema’, partially because we can’t exactly have a new new wave of Australian cinema, and also because the proliferation of independent voices is seeping across the nation like a slow-moving flood, permeating the soil and causing fields of everlasting voices to emerge. A movement - a change - doesn't happen overnight, and often it's only perceived in retrospect, not while it's in motion. This rising swell exists out of neglect and as an act of defiance against the (perceived) box ticking nature of funding bodies. In the past few years, the cast of independent filmmakers across Australia has increased.

Filmmakers like Jacob Richardson (The Aegean), Glenn Triggs (Ancestry Road), Bina Bhattacharya (From All Sides), Matthew Holmes (Fear Below), Emilie Lowe (The Canary), Peter Skinner (Two Ugly People), Troy Blackman (Vineyard Ablaze), Mara Jean Quinn (Andamooka), Adrian Ortega (Westgate), Jane Larkin (The Edge), and many, many more are pushing forward by telling uniquely independent stories from their unique perspectives.

Many of the names in the below list are part of that growing movement. Collectively, their work is setting the trend for what this rising swell of Australian cinema looks like. While it might feel like the swell is in its nascent state, these are filmmakers who have been shifting what the definition of an Australian film is. Sure, they're not all great films, sometimes they're thrown together over many years of borrowed weekends, sometimes in hours across a day or two, but what links them all is the collaborative thirst for uniquely Australian storytelling and, more importantly, crafting something that they want to see. After all, if you are your own audience member, then there's going to be someone just like you interested in what you have to share with the world.

With that comes a shaking off of an array of identities that has burdened Australian cinema for a long time. Like 2024, Aussie comedies were fucking funny with jokes that cut through like an acid bath this year, even if audiences were denied chances to see them. The 'crime in a country town' trope seems to have been safely cordoned off on streaming services, almost to the point of nullifying the presence of the Aussie crime drama. While we're still getting the obligatory annual 'adult kids looking after elderly parents' flick in the form of Bruce Beresford's The Travellers, we are seemingly opening up to having more open conversations about death, dying, and what it means to be an elderly person living in Australia right now (Edge of Life - Lynette Wallworth, Careless - Sue Thomson). Horror continues to make its mark and show that when filmmakers are given judgement free support, they can make some messed up shit that leaves a mark - see: Bring Her Back, Together, Dangerous Animals. Multicultural and queer voices continue to make films with their communities about their communities; see Bina Bhattacharya's From All Sides as a rare example of a genuinely sexy film that presents multicultural, queer Australia from a lived-in perspective, or for a more family friendly flick, there's the multi-narrative My Melbourne (directed by Onir, Rima Das, Arif Ali, Kabir Khan, Imtiaz Ali, Rahul Vohra, Samira Cox, William Duan, Puneet Gulati, Zhao Tammy Yang).

In Lonely Spirits and the King: An Australian Film Book, I rabbited on at length about why Australian cinema means something to me, but the core reason is about making sense of this conflicted nation. I like seeing Australian stories on screen. I like seeing global stories told by Australian filmmakers. I like seeing global filmmakers telling Australian stories. I love experiencing the ways Australian filmmakers recontextualise this nation, making sense of its existence, while also adding their own sentence to the novel that is Australian culture. Some of the Aussie films from 2025 managed to do just that, while others expanded their scope and gave space to the stories that are occurring globally in this ever-conflicted world.

However, what I really love about Australian films is that sense of discovering the stories that are eager to burrow their way into my dreams. Sometimes those films stoke nightmares and vibes of repulsion, while others fritz their way into my head, altering how I see my view of Australia. Sometimes I'll be walking down the street and am certain I've just seen Em and Jessie from Fwends heading down a side alley. Other times I wake at 2:13am, unnerved by the memory of a young boy gnawing at a kitchen bench, his stomach growling as it grows in size. Then there are the times that I drift off to sleep with the sounds of Warren Ellis on a violin playing to the inhabitants of a wildlife sanctuary as dusk creeps around them all.

I’m not sure how my sleep will go in 2026.

Even with the long-promised content quotas now on the way, I think I’ll still have pitiful dreams about the Australian film industry and the difficulties it's facing with reaching audiences. I'll no doubt continue to be haunted by that recurring dream of sitting in a cinema alone watching the best Australian film I've ever seen and rushing out to shout about its existence to the world, only to be greeted by a chorus of people saying 'never heard of it' 'nah, I don't watch Australian films' 'Australia hasn't made a good film since The Castle'.

I’ll still be searching for those Australian films that I feel stand confidently alongside the best of global cinema. I'll take immense pride in championing and advocating for independent filmmakers, artists, and storytellers, providing a platform to amplify and share the work - it's not fucking content - that they create.

As my focus has shifted from writing film reviews to being an almost permanent interviewer, I've relished the joy of hearing stories from filmmakers about their work. It is a rare privilege to share the stories of filmmakers with the world and to introduce you to their film. I don't take what I get to do lightly, and am forever grateful that I am even able to talk to anybody about their films.

If you've listened to or read any of the pieces we've published on the Curb across the past year: Thank you.

If this is your first time reading a post from the Curb: Welcome. We hope you enjoy what we've got going on here and stick around.

Anyhow, enough rambling, this is supposed to be a positive list that tells you about what I feel are the best Aussie films of the year, right?[3]

So, let me tell you about the films that kept me up at night in a good way as they replayed themselves in my mind, their images dancing across my memories and pulling out their emotions for me to sit and contemplate them once more.

Before I delve into those favourite Australian films of 2025, here’s a slice of the favourite Aussie films from the readers of the Curb:

Lesbian Space Princess! – Fiona Underhill @fionaunderhill.bsky.social, writer for IndieWire, SlashFilm, Nerdist, Crooked Marquee, MovieJawn, Filmotomy, The Digital Fix, Girls on Tops

Lesbian Space Princess – Lili @lilifilms15.bsky.social, screenwriter/director

Lesbian Space Princess – Alaisdair Leith, Novastream

The one I enjoyed the most: Together. The one I'd like to set a trend: Head South. The one I'd show my American friends: One More Shot. – Leon Moor

Dangerous Animals & Inside – Kate Separovich, producer of Proclivitas

Kangaroo edging out Primitive War – TL;DR Reviews @tldrmovrev.bsky.social

Without a doubt… Bring Her Back – Bede Jermyn @bedejermyn.bsky.social

Inside – Jason Harris

Bring Her Back is one of my favourite films of this year. It’s doomy, gloomy, and just so incredibly bleak – right up my alley. Surprisingly emotional as well. Absolutely loved the hauntingly beautiful score by Cornel Wilczek, which really enhances that feeling of dread. Beautiful cinematography too, and such fantastic performances from Sally Hawkins, Billy Barratt, Jonah Wren Phillips and Sora Wong. This is one of those films that benefits from a rewatch, and the ending still hits as hard as the first time, it had me sobbing again when I rewatched it. Other Aussie films I really enjoyed are Dangerous Animals, The Surfer and Together. – Lisa Cooper @lisa_cooper91

Rotten!! It’s an awesome Aussie horror with a side of dark humour. – Hannah Brooke @hannahzbrooke

Together & Dangerous Animals. Both so much fun. Loving the new age of Australian horror! – Frances Elliott, co-director of Girl Like You and Renee Gracie: Fireproof

Kangaroo Island, Dangerous Animals, Kangaroo, Yurlu | Country – The Popcorn Panel @thepopcornpanel

The Golden Spurtle was one of my favourite films of the year. Also had a lot of love for; Bring Her Back, A Grand Mockery, Inside, Dangerous Animals, The Surfer, Ellis Park - Mitch Bozzetto

For another list about Australian films from 2025, read Cinema Australia's list of films they watched here:

Andy Hazel with his top ten Australian films list:

10. Journey Home, David Gulpilil

9. The Surfer

8. Dangerous Animals

7. Lesbian Space Princess

6. The Bad Guys 2

5. Head South

4. Inside

3. The Golden Spurtle

2. First Light

1. Ellis Park

Due to the fluid nature of Australian film release dates, some of the titles that received wider releases in 2025 appeared on the 2024 list, such as Every Little Thing and Stubbornly Here, while some of the titles viewed in 2025 may appear on the 2026 list (see: Birthright, Pasa Faho, We Bury the Dead, First Light, Iron Winter).

Films that were released in various forms but not viewed by me included: Welcome Back to My Channel - Jorrden Daley, Within the Pines - Paul Evans Thomas, It Will Find You - Chris Broadbent, Enzo Tedeschi, Freelance - John Balazs, The Household - Luke Shaw, Dropbear - John deCaux.

A list of Australian films released in 2025 via theatrical release, festival runs, streaming runs, or other, can be found via this Letterboxd list. Of the films on the list, I saw 68 Australian feature films and lost count of how many short films released in 2025.

Finally, I want to shout of Jason Raftopoulous’ Voices in Deep which suffered the cruel fate of being a film that emerged on the fringes of film distribution, receiving a screening or two here and there across the past few years before any kind of conversation about it took place. It missed the 2024 list, and it's not on this list, but I'm shouting it out as it's as urgent and vital as his debut film West of Sunshine, and like that essential drama, it would have featured high on a best of list. This is the kind of film for those who look at European cinema and say ‘why can’t Australian films be more like them?’ I chatted with Jason early in 2025, and you can (and should) listen to that chat here. It's one of my favourite conversations from 2025.

To read previous Best of Australian Film annual lists, visit the links below:

2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should note that this article features images and the names of deceased people.

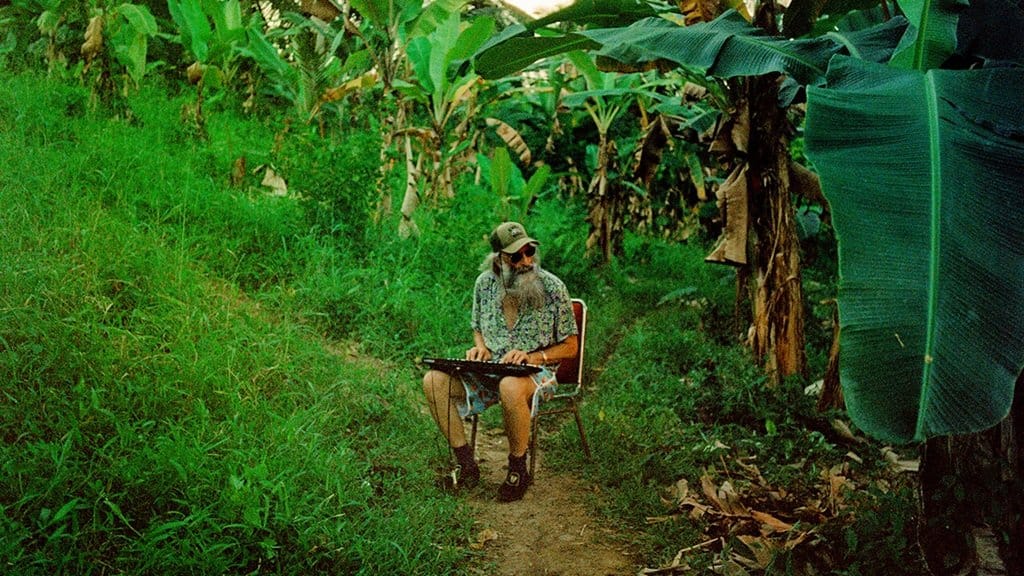

Justin Kurzel's first documentary, Ellis Park, acts as a dual experience: firstly, we follow musician Warren Ellis as he revisits his hometown, spends time with his parents, plays music for Kurzel in an empty cinema, talks about the importance of Nina Simone’s gum, and then, we learn of his decision process behind financially supporting the Jakarta Animal Aid Network. In its second half, Ellis Park shifts to exploring the way that the carers of rescued wildlife at Ellis Park Sumatra and the Jakarta Animal Aid Network work to combat the illegal wildlife trade and aim to improve animal welfare in Indonesia, while also meeting animals like Rina the primate and Erin the elephant who have found themselves in their care.

Ellis Park is a compelling and visceral addition to Justin Kurzel’s growing assessment of the reverberating impact of trauma. Kurzel’s films are often violent and leave scars, and there are moments in Ellis Park that will do just that; the presentation of documented cruelty underlines the importance of the wildlife carers, but the presentation of animal trafficking and the horrific injuries they gain during the process is overwhelming to point of emotional devastation. Trauma begets trauma. Kurzel does work towards a point of emotional healing for the audience as he utilises Germain McMicking’s immersive cinematography and Ellis’ violin to ease our souls, but we’re left to wonder how much healing will mend the wounds of the animals of the park.

Listen to Justin Kurzel talk about the film in this interview:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Mother of Chooks is a disarming film in the way it put forwards a charming, sweet, cynicism-free experience, inviting you to put aside your woes and enjoy the delight of getting to see subject Elaine James and her flock of chooks sit at her dining table as she runs through what their day looks like. Co-directed by mother and son duo Maite Martin Samos and Jesse Leaman, Mother of Chooks is the kind of film you didn’t know you needed, but when you invite it into your heart, you’ll be grateful for the dreams you’ll have after seeing a frizzle at the beach.

That warmth extends to the community which emerges around Elaine and her chooks; Elaine takes her flock down to the beach, or to the café, or socialising with friends around her home of Geelong. They meet a glorious Isa Brown named Flapper, or the group of bantams or frizzles which look up to Elaine as a mum. There’s a judgement free perspective here driven by an all-embracing understanding that when we invite our fellow living creatures into our lives that they have as much love to give us as we do them.

Listen to this interview with Jesse Leaman here:

Australia’s relationship with incarceration is one that goes back to the foundation of this invaded land. On a cinematic level, we tend to see dramatised stories about prison life, but it's not often that we get to step inside prison and hear stories from those who have found themselves serving a sentence. Shalom Almond spent six-months with the women of the Adelaide Women’s Prison, documenting their musical journey as they learn how to write songs, to sing, and to play the ukulele in preparation for a performance with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra in front of their fellow inmates.

What the women did to be prisoners is of no importance; their journey forward to parole and returning to life outside is what matters, and it’s through that healing music journey that makes Songs Inside such an impactful experience. This is selfless storytelling, empathy-forward filmmaking. Songs Inside is an earnest documentary that asks audiences to remove judgement and to consider that people can have their lives thrown out of orbit, only to be brought back onto the path to return to their connected community through programs like this.

Listen to this interview with Shalom Almond about Songs Inside here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Featuring an always-welcome lead turn from Emily Browning, who is comfortably supported by some of the finest Aussie actors right now (Sean Keenan, Ashley Zukerman, Aisha Dee), One More Shot takes the neat concept of a time travelling bottle of tequila blended with the turn of the millennium and the threat of Y2K, plus a whole bunch of reflection, regret, and hopeful relationship restoration, to become a delightfully charming comedy full of pep. It’s New Years Eve and the fucked up things of the past are about to be fixed for good one shot at a time.

On paper, time loop stories seem simple and easy to create. Depending on the length of the loop and what happens during it, they can be a cost-effective way to create a genre-based story that can work in a single location with minimal costume changes. There’s been a few Aussie films over the years to dabble in the subgenre – Predestination and The Infinite Man being notable examples of strong sci-fi efforts – but Nicholas Clifford’s feature debut One More Shot is the lightest and funniest one of the bunch. It helps that Clifford’s got one heck of a script from Alice Foulcher & Gregory Erdstein (it’s been too long between drinks since That’s Not Me) to work with, giving him and his cast a playground to work in that reminds audiences that Australian films don’t always have to be doomy and gloomy. They can be funny as fuck too; a nice trend that continued throughout the year.

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Speaking of comedy, there’s something awfully perverse about bringing Nic Cage to the stunning South West of Western Australia to play a bugged out bloke trying to buy his family home at Christmas time, and then effectively locking him in a sandy, sweaty carpark next to the beach and made to wear the same, grimy suit for the whole shoot. They don’t even give him a name, he’s just ‘the Surfer’.

But it’s Nic Cage, why would he need to be anywhere other than in a box, bouncing around, soaked in sweat, trying to pay for his flat white, unable to fill up his water bottle and having to resort to chowing down on a rat instead?

The Surfer isn’t just Nic Cage being Nic Cage. Director Lorcan Finnegan stacks the supporting cast with a chorus of stellar performers: Justin Rosniak, Alexander Bertrand, Rahel Romahn, Miranda Tapsell, and the late great Julian McMahon. This troupe of Aussies ramps up the strine, making The Surfer play out like a documentary at times. Julian McMahon’s towel poncho adorned Scally stands as a surrogate ringleader to his flock of lost boys, each muttering their trance like mantra ‘don’t live here, don’t surf here’ to anyone who will listen.

With The Surfer, Finnegan and writer Thomas Martin have catalogued sects of modern Australia as outsiders peering in, observing the cliques that stomp on the shores and scour the streets, pushing out anyone who doesn’t look or sound like them. The Surfer has been compared to Wake in Fright and The Swimmer, and sure, they’re all part of similar a thematic brethren, but there’s a singularity to The Surfer which makes it stand out as an anomaly within Australian cinema: an Australian film, made by an outsider peering in the box and saying, “Australia, what fresh hell is this?”

Listen to this interview with producer Robert Connolly about working with Nic Cage here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Darwin Schulze’s Bluebird is more than an ode to a genre of storytelling that has long subsided into the past, it’s a gloriously green reminder of what is possible within independent filmmaking. Schulze taps into the heyday of adventure films, tapping his hat briefly to the glory days of screen musicals, all the while envisioning a better live-action version of Disney films than the House of Mouse is capable of.

Annabel Wolfe is Bluebird’s heroine, a princess seeking to save her true love from bandits. Wolfe owns the screen comfortably, sharing it with the titular bird, a charming puppet creation that adds to the sense of whimsy and playfulness across the film. Schulze and co-writer Eric Zac Perry toy with motifs in such a tender manner, flitting from musical, to fairy tale, to an epic adventure, before finally closing on a sword and arrow fight in the darkness, and you can’t help but get swept up in the delight of it all along the way.

Short films are often seen as calling cards for creatives, as a brief showcase of what they’re capable of, and if Bluebird is anything to go by, we’re in for a treat as the career of Darwin Schuzle unfurls.

Listen to director Darwin Schulze talk about bringing adventure back to Australian screens here:

Watch Bluebird here:

The below piece was included in the moviejuice zine for when Night Walks screened at their SMORGASBORD screening.

In their jaunty 2007 song, The Panda Band dubbed Perth as being a Sleepy Little Deathtoll Town, a place where people have pretty neon veins. In 1962, astronaut John Glenn floated over Earth, glancing down to see Perth city in a bath of brightness. He dubbed this isolated hole of existence ‘the City of Light’, yet if he walked the streets of Perth, he’d find lots of nothing.

In Jacob Brinkworth’s slow-cinema mood experience Night Walks, light cuts through the sanctuary of night, illuminating the two nameless characters who exist as inert beings stifled by modernity and trapped in the purgatory of Perth. ‘Remember weekends?’ one asks the other as they sit in the stifling silence of a well-manicured park at night, ‘We used to have them as kids.’

Night Walks is as desolate a reaction to Dullsville as I’ve ever experienced. Life, living, and senses of self are smothered in a city where mining dictates the shape of the skyline and our unceasing work-life balance is skewed heavily towards the bean counters.

But what of that work? Jacob presents that daily toil as an act of sitting in soulless, spiritless offices, whiling away the hours achieving nothing but existence itself. Why leave the office when the nothing that exists outside of its walls is just a different shade of grey? As the decades have worn on, government after government has tried to jump up high and get the world to notice pitiful Perth, but it’s reactionary filmmakers like Boorloo-born Jacob Brinkworth who bring this solemn city to its attention.

‘The world's gone to sleep without us,’ one character remarks, but Jacob Brinkworth never stops dreaming.

William Jaka and Fraser Pemberton’s Faceless is one of two films shot in Naarm-Melbourne that feature on this list which invited viewers to see the city anew. Faceless presents a triptych of stories, from the dark banks of the Birrarung-Ga where soldiers turned rough sleepers find sanctuary under the Princes Bridge, to the art dens on street level where creativity persists as if it's crafted from 'experience' (but really it's just trauma mining other cultures existence), and then, high above in the golden sheen of prestigious mining-money driven restaurants where mining dollars crack the shells of hundred dollar crayfish. On each level, denizens declare foundational rights while Jaka’s Indigenous Faceless Man feels himself become further disconnected from his own land.

Jaka and Pemberton are part of a creative collective called Dogmilk Films, spread across countries and creatively curating a singular style of storytelling that is uniquely their own. Made under the Dogmilk Films banner, Faceless is a slice of co-authored cinema that actively stokes the role of storytelling in our world, reminding us that while we may each walk on the same land using similar words to call these places home, we do so with a different understanding of their past, present, and future and the stories they hold inside them. Faceless embeds those layers of history in each frame, outlining the way it’s laying the path for the future, and in the process, Jaka and Pemberton ask: is anguish art, or is it something we can grow away from?

Listen to co-directors William Jaka and Fraser Pemberton talk about their collaborative approach to filmmaking here:

Watching Andy Johnston’s gentle short film Coming & Going highlighted just how many Aussie queer films are tinged with trauma or overt drama. This kind film tells the story of two strangers – Harry (Michael Nikou) and Julian (Ilai Swindells) – who make the decision to be boyfriends for a week before Harry returns home. Johnston centres Australian male queer love in a way that feels like a gift, or as I mentioned when I interviewed Andy in 2025, as if the film is the start of a quiet revolution within the Aussie queer film scene.

Coming & Going was influenced by a brief relationship that Andy had in Canada with co-writer Anthony Filangeri, creating a lived-in presentation of the queer male experience that honours the beat of the heart that comes with being close to someone who sees you, understands you, desires you, in a way that others haven’t before. There are moments of affection between Harry and Julian that feel as if we, the audience, is invading on their privacy, but those moments are also paired with Andy’s invitation to witness their love and desire for one another. Nikou and Swindells are perfectly paired with their genuine chemistry giving a well-earned weight to their final scene which evokes that strong sense of yearning that was so keenly felt at the close of Past Lives or Before Sunrise.

(Coming & Going is not the only film from 2025 that pulled from past relationships to create the foundation for an on screen connection. Daniel Bibby's impressive short Half Past Midnight touches on the echoes of a past relationship and how the memory of it lingers in his present.)

If this is the style of queer storytelling that Andy Johnston is going to craft in Australia with his production company Dandy Films, then I sense the oncoming of a great queer awakening on the horizon.

Listen to director Andy Johnston talk about the tenderness of Coming & Going here:

I thought a lot about pleasure while watching Daniel Tune's societally stunted Malls, an ode to the loneliest places of all: public spaces. We follow Noodles (Gabe Bath) and Lou (Emily Pottinger), never named, but physically present on the streets of Adelaide, wandering in search of purpose and connection. He consumes a selection of Adelaide's finest fast food offerings, while she hangs on telephones waiting for some kind of answer. He occasionally eats hotdogs out of puddles or KFC in alleyways while she tries to lay an opportune peck on an ad featuring Ryan Gosling or trying to climb up to give a statue of a soldier a kiss.

Noodles and Lou exist on the streets of Adelaide under the shadows of buildings that sell the promises of new lives, of holding onto hope, of fractured capitalistic nonsense phrases like 'Help People Help Planet', and even with the promise of reinventing your orgasms. These empty promises and sales pitches are bathed in the artificial golden hue of the omnipresent giant M that marks the respawn location that is your local Maccas. None of these things are accessible to the characters of Malls, and it's that inaccessibility that makes the film feel like you're watching a mirror at times.

Inspired by the silent characters of a Tsai Ming-liang film, Tune's soundscape becomes a symphony of Pavlovian beeps, the screech of brakes, and the unceasing churn of construction and growth rings through the air. This is the familiar audio experience of our capital cities. The corporatised existence we live in means the vistas of Adelaide is transferrable to the vistas of Perth or Brisbane. Sure, the skyline is a little different, but they each have their own vacant office buildings, promises of reinvented orgasms, and the thought stifling magnitude of this thing we call 'modern civilisation'.

Malls explores the notion of pleasure, with Noodles sitting on the pavement, constructing a home he'll never fit in, a mini-church made out of Lego, its chosen deity is a clown named Ronald. When Lou briefly visits her home, she finds herself trapped in the gaze of her phone - always consume, always be sold to, always be buying. Privacy doesn't exist anymore, and while you can gorge yourself on a succulent KFC burger in an alley way, you do so under the gaze of the eyes of corporations observing you, algorithmically and obsessively tracking what food you eat, what sauces you choose, knowing that you'll buy the barbecue sauce from Hungry Jack's but the smoky chipotle sauce from KFC.

Pleasure and self-satisfaction are boundary locked items, restricted as we grind away doing fetch quests and menial tasks, forever being unable to reach an ever-increasing level cap of privilege. Malls then becomes a bit of a joke at times, encouraging us to laugh at our reflective existence, all the while encouraging us to take a bite of that puddle hotdog. It's as if Tune is saying, 'hey, this may be the highlight of your day, and if your lucky, it might be the highlight of your year.' Near its close, Noodles and Lou are afforded an illusory dream of pashing madly on the Adelaide Riverbank Pedestrian Bridge.

But you can't pash in public like that. That kind of pleasure is for your mind only.

The moviejuice crew - Daniel Tune, Emily Pottinger, Gabe Bath, everyone else under that umbrella - are reshaping what South Australian cinema looks like. Malls is a real treat, a bit like sticking fries on your cheeseburger.

For further exploration of Daniel & Gabe's work, I encourage you to read Indigo Bailey's piece about Malls and Ships That Bear here:

In her documentary Make it Look Real, Kate Blackmore follows director Kieran Darcy-Smith as he works through creating Tightrope, a film constructed for the purpose of this documentary. In the scripting and rehearsal process, Kieran and his actors, Sarah Roberts, Albert Mwangi, and Tom Davis, each engage in a dialogue with intimacy coordinator Claire Warden as she talks through how to safely present simulated sex scenes for all actors, ensuring that body autonomy and respect is maintained along the way.

Make It Look Real would be a compelling experience if it solely focused on the way that Claire Warden embeds safe practices through consultative and collaborative process to present simulated sex on screen, but it shifts into ‘must view’ territory as Blackmore expands on the history of sex and nudity on screen, outlining why intimacy coordinators are becoming a useful resource utilised on film and TV productions. Blackmore explores how films like Last Tango in Paris created an unsafe space for the lead actress, before exploring how actresses across different films have felt pressured or obliged to do a nude scene or present a sex scene they may have otherwise not have wanted to do.

Blackmore skews away from turning Make it Look Real into a directive film, focusing on making an engaging documentary first, and a film that suggests a way of working second. In that regard, Make it Look Real becomes a conversation starter that opens the door to how the ways of working on a set can change to be safe for all.

Listen to producer Bethany Bruce here:

And director Kate Blackmore here:

And performer Albert Mwangi here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Kristoffer Lucia’s Chokeberries is nine-minutes of a breathless run of coked up monologues, rambling trauma-dumps, sozzled pool-side soliloquies, and mumbled moaning through the soap of a toothbrush as Elizabeth (Franca Lafosse) and Jojo (Shant Becker) divulge their petty emotions about their breakup to whoever and whatever will listen to them. Pulsing with a score by Jaw-Moss, Chokeberries bumps and grinds its way through a catalogue of characters who feel ripped from the last house party you went to or from that session at your local just before last drinks are called.

There’s a kinetic energy that keeps Chokeberries moving, the kind that is rarely tapped into in Australian cinema. 'Make what you know' is the directive often given to emerging filmmakers, and sure enough, Kristoffer Lucia has done just that. I watched Chokeberries at Perth’s Revelation Film Festival, and it felt like I was watching something perverse, something illicit and creatively progressive. I’ve been impressed by the magnetic quality of filmmaking coming out of South Australia right now with filmmakers like Lucia and Daniel Tune simply not giving a fuck about what they should or shouldn’t be making, and instead crafting something that’s truly singular and representative of their cinematic culture and creativity. It’s bloody invigorating and thrilling to experience. More please.

For performance artist Stelarc, the body is a tool which invites an investigation of pain and discomfort. If there is an audience viewing him hanging from a tree by the hooks in his back, then they too are invited to question what the role of pain and discomfort is in art and living. But, if they’re like me, they might find themselves transposed into a rather tranquil state of being, passively engaging in the transcendence of another as they extend their body to its limits. As someone who has found great catharsis in getting a tattoo, I can only imaging the mental state that comes with hanging naked from a tree with a series of hooks in your back.

Stelarc Suspending Disbelief is the work of co-directors Richard Moore and John Dogget Williams, collaborators who have witnessed Stelarc’s career over the decades and invite us to watch his creative journey as an artist exploring the intersection of humanity and technology over the decades. Like a spider spreading its web, Stelarc Suspending Disbelief introduces the audience to other performance artists, with the film notably reaching towards the nausea-inducing button as a montage of artists whip themselves, pierce their skin with metal, or brutally hack off their own arm.

It’s a strange thing to watch a film like Stelarc Suspending Disbelief and be entranced by it and find a solemn beauty with Stelarc’s ageing body and his push to continue performing and forging that connection between body and technology; as he ages, he can’t do the extreme body acts as much as he used to, leading to the creation of things like a third arm, a prosthetic head, or a cyborg controlled by strangers.

On a visual level, I was able to understand my relationship with pain more by watching this film. My chronic illness means I’m often waking in pain or aching, leading my physicality to feel like it’s being dominated by something I can’t control. Watching Stelarc controlling and managing pain in the way he does made me feel the sensation of body doubling, giving way to a physicality and pain that was not my own. I was able to transfer some of my own pain onto the images of Stelarc hanging from trees or watching that man cut his arm off.

“The body is obsolete” is Stelarc’s mantra, and that’s a mantra that’s stuck with me since watching this film. My body is obsolete in the shadow of the pain and fatigue it experiences. Even writing this piece is causing my body to become even more obsolete, with each key stroke adding a cup to the well of pain that will be drained once my pain relief kicks in. But, the thing that might be hard to understand for those who aren’t in a constant state of pain is that pain can be calming, pain can create a reliable state of mind, pain can be a source of comfort. If I’m in pain, then I know what my base level of existence is for the day. When I take pain relief (which I do want to stress is a salvation, I’m not actively yearning to be in pain every day), my conscious state is one of waiting for the pain to return.

That mindset is amplified by Stelarc’s interspersed conversations with comedian and disability advocate Liz Carr who explore what the role of art and disability and pain is. These moments are compelling and captivating, and when paired with the visceral art of Stelarc, Stelarc Suspending Disbelief becomes a work of transcendent brilliance.

Listen to co-director Richard Moore talk about the provocative nature of Stelarc Suspending Disbelief here:

Within the opening moments of Domini Marshall’s immersive short film Howl, we’re invited into the headspace and worldview of Daisy (Ingrid Torelli), a teen woman on the cusp of adulthood heading to a house party. We meet her at a train station, waiting for the next one to arrive. She’s in a state of hyper vigilance and uncomfortable in her own body, a notion amplified by her oversized shirt and hair that drapes over her face. As the night rolls on, Daisy’s relationship with Lila (Kristina Bogic) encourages an understanding of herself and who she is as a person.

Ingrid Torelli gave an impressive turn in Late Night with the Devil, and in Howl she shifts forward as an actor, delivering a grounded and relatable performance that will hopefully give way to more characters like Daisy. She’s comfortably supported by Marshall as a writer-director, and also by producer Josie Baynes, someone who is quickly becoming a talent on the rise with films like Howl, Hafekasi, and Stranger Brother under her belt. Tying Howl together is Matthew Chuang’s cinematography which shows his clear ability to immerse viewers in the mindset of the characters. Each of these names are people to watch out for; there’s some great work brewing within their minds.

Listen to writer-director Domini Marshall & producer Josie Baynes here:

And cinematographer Matthew Chuang here:

If 2023’s Linda 4 Eva wasn’t enough to put Sophie Somerville on your map, then her feature film debut Fwends, which won the Berlinale Forum’s Caligari Film Prize and received an AACTA award nomination for Best Indie Film, will.

Like William Jaka and Fraser Pemberton’s Faceless, Fwends invites a rediscovery of Naarm-Melbourne as cinematographer Carter Looker’s roving camera captures fwends Jessie (Melissa Gan) and Em (Emmanuelle Mattana) as they spend a weekend in the city reuniting, reminiscing, and unconsciously testing the future of their fwendship. They traipse down side streets, walk along the shore of the Birrarung-Ga, enter the comfort of a hidden garden, and reforge a connection with each other and the city Jessie calls home.

I revisited Naarm-Melbourne for the first time since pre-pandemic times early in 2025 and I felt like I was walking in a changed city. I stepped down streets, anticipating the same old feelings I had, only to find myself in a different world. As Fwends progresses, that feeling of being at a home that you don’t recognise sinks in. There’s affection for it, and the grooves on the paths feel awfully familiar, but the complexity of the present makes sitting with the memories feel complicated, like a piano that’s playing with one key out of tune.

But that’s what makes Fwends soar; it’s a film that is cognisant of the way that we grow, and change, and turn into older people with memories and feelings trapped within us. As the title suggests, there’s a level of whimsy and charm to Somerville’s film, all of which creates a lightness that makes spending time with Jessie and Em feel just lovely, even as the creeping sense of disconnect between friends sinks in as their story progresses. It then says, those memories are true and those feelings are valid, but remember what helped forge those memories in the first place: true fwendship and the bonds that make us want – to crave – to spend time with someone else. It’s silly moments of wearing face masks and singing into microphones and inviting someone into your sacred space, and it’s those moments that we need to remember as distance and space creeps in to make its presence known.

Fwends is beautiful and delightful vibe-based filmmaking at work. Here’s to the growing filmography of Sophie Somerville.

Read Cody Allen’s review here:

And listen to Nadine Whitney’s interview with Sophie Somerville here:

Watching actors evolve on screen is a fascinating thing to witness. Dacre Montgomery has been compelling in genre-fare like Power Rangers and The Broken Hearts Gallery, but watching his performance alongside Vicky Krieps in Samuel Van Grinsven’s Went Up the Hill felt like the next stage of a great talent emerging. Anguish, frustration, grief, and the search for resolving generational trauma sits at the core of Montgomery’s performance as Jack, a man returning home to the funeral of his estranged mother, Elizabeth. He meets Jill (Krieps), Elizabeth’s widow, and the two work through their grief and sorrow in the unhealthiest way possible. Sure, it doesn’t help that they both get possessed by the spirit of Elizabeth, leading to scenes where a soundtrack of haunting, howling winds add weight to pockets of this Australian (by way of Aotearoa) gothic.

Went Up the Hill is as serious as its gets, with Van Grinsven leaning into a hard arthouse vibe that might turn off some viewers. For me though, that seriousness gave Montgomery the ability to step up his acting game, with the Boorloo-local actor comfortably sparring against the great talent that is Vicky Krieps. The two actors are supported by the brutalist, cold architecture of the house they reside in, with Tyson Perkins grey-soaked cinematography draping Jack & Jill’s narrative in a coldness that will have you reaching for a jumper to keep you warm.

With Went Up the Hill and his frazzled and tense turn in Gus van Sant’s 70s-era thriller Dead Man’s Wire under his belt, and the promise of a feature directorial debut (The Engagement Party), Dacre Montgomery’s time is now.

Read Nadine Whitney’s review for Went Up the Hill here:

And listen to Dacre Montgomery here:

And director Samuel van Grinsven here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Sometimes the most obvious analogy for a film is the most apt:

The Golden Spurtle is like eating the very best, warmest bowl of porridge on the coldest day you’ve ever experienced. Constantine Costi’s documentary is like walking towards the most inviting Scottish building you’ve ever seen and smelling the crushed green grass under your feet as you get closer. It’s like hearing your grandparents talk about home again and tell you stories about what growing up in wartime was like when simple food brought simple pleasures. This is the kind of film that’s about a home you didn’t know you had thousands of kilometres away from you.

Cinema, like food, is a great transporter to the past, or to a feeling you didn’t know you could have ever again. While some might say what I felt while watching The Golden Spurtle was a form of nostalgia, what I think I felt was a sense of belonging.

There’s a moment in The Golden Spurtle where the Porridge Chieftain places a small figure of himself in a replica of the building where the World Porridge Championship is held, and I had to do everything in my might to hold back tears. I felt a connection with my heritage in a way that I’ve not really felt before in an Australian film and for that, I’m forever grateful.

Read Cody Allen’s review of The Golden Spurtle here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

The one song I listened to the most in 2025 was Julia Jacklin’s cover of The Boys Next Door’s Shivers. What was originally intended as an ironic and humourous track with a streak of cynicism has become a bit of a touchstone for artists across the globe to cover it. Cat Power, Courtney Barnett, The Screaming Jets, Folk Bitch Trio, and, the one that fits my sensibility, Julia Jacklin. I tend to listen to the studio version in the shower, but keep the first thirty seconds of it a bit low as to not concern my partner with the first line:

I’ve been contemplating suicide

I think my fasciation with Jacklin’s take on Shivers started a little bit after I watched Giles Chan’s Jellyfish at the 2025 leg of the WA Made Film Festival. The film is an essay on mental health – or maybe rather, what happens when someone doesn’t know they’re depressed and living a fucked up existence.

My baby’s so vain

She is almost a mirror

Those lines ring in my ears as I think of Jellyfish, a film that took a melon ball scraper to my insides and left me hollowed out like no other film did in 2025. At its close, when the lead character walks into the ocean and never returns, I felt like I was watching a mirror. I’m, thankfully, doing better now, and I think it’s because of getting to see someone else go through an experience that is almost a mirror of what I went through eight years ago.

The circular line running through my mind of ‘I’ve been contemplating suicide’ doesn’t mean I’m thinking about going down that path, but rather, I can’t stop contemplating the presentation of suicide in media. When it comes to male suicide on screen, there are some common reactions: ‘they didn’t do anything to better themselves’, ‘they rejected help’, ‘it’s almost like they didn’t know they were depressed’, amongst many other reactions.

Jellyfish is a bleak film, and that’s fair, because suicide is bleak. Chan’s filmmaking reminds us that not every film needs to have some kind of redemption arc or full of characters who magically get a self-realisation of the level of despair they’re in. People who die from suicide don’t get that arc in their lives, and it’s comforting for me to know that art like Jellyfish exists as a testament to those who can’t better themselves because they have no idea that they’re in a spiral of nothing.

Like Stelarc Suspending Disbelief, Jellyfish helped contextualise my own existence in a way that I haven’t had before. Maybe this is why I didn’t sleep well in 2025. Maybe reminders of the past are poor ways of progressing positively into the future. Either way, I’ll keep listening to Julia Jacklin in the shower (although I’ll stick with listening to Pressure to Party a little more often than Shivers) and I’ll keep being grateful that Giles Chan has made this ode to painful existences.

Read my review of Jellyfish here:

Listen to Giles Chan talk about Jellyfish here:

https://www.thecurb.com.au/jellyfish-interview-giles-chan/

There’s a few films on this list that were hobbled by poor audience reach and accessibility, and Angus Kirby’s sexy and shockingly hilarious body swap comedy Carnal Vessels is right up there as being hard done by. Screening at a handful of film festivals before being shuffled online, Carnal Vessels is at once a reminder that Australian comedies do exist and they are often very, very good.

Olivia (a luminous Arnijka Larcombe-Weate) and Alex (a charming Daniel Simpson) are kinda partners, kinda fuck buddies, but definitely close friends. He works in a cemetery, she sometimes sleeps with James (Dylan Stumer), a bit of an odd bloke. One night, Olivia and Alex have sex and somehow, someway, they swap bodies. What eventuates is a comically grounded exploration of two people who start to become comfortable in the body of their friend, all the while discovering the lives they each live.

Kirby is smart enough to know not to try to explain the whole body swap part of things, and in one of the best, riskiest moves, he also lets his characters just… live with it, rather than trying to find a way to get back into their own bodies right away. What that means is that he cuts out a lot of the plotting and navigation that often drags down body swap comedies where characters just have to get back to being themselves. Instead, Olivia and Alex start to stretch and get comfortable in their surrogate bodies. Kirby leans into the raunch of the title, embedding a rarely seen array of sex and nudity in the film, both of which strengthens Olivia and Alex as characters.

The key to the comedic success of Carnal Vessels comes in the form of the chemistry between Arnijka Larcombe-Weate and Daniel Simpson, both of whom ought to be stars after their turns here. (Seriously casting directors, look out for these two, put them on your lists, they will make your film better.) Arnijka carries herself with such ease, confidently employing the swagger of a tall man trapped in a shorter persons body, and retaining the self-confidence that comes with it. Daniel somehow manages to showcase what it feels like to be a woman finding her way in the body of a tall man, and in his performance you can feel Olivia stretching out into Alex’s skin. It’s quite the thing to watch.

Carnal Vessels stumbles a fraction in its closing third, but it’s not enough to throw off what is a superbly scripted comedy. Aussie filmmakers take note: this is what happens when you hone and craft and work on your script long before shooting and you give your actors the space to play, to enjoy building characters who audiences will want to spend time with. This, alongside one of the future entries, is one of the tightest scripts of 2025.

I should also quickly shout out the cinematography of Elliott Deem who captures colours and shots in a way that elevates the already great performances and script. I hope this isn’t the last time we get to see Kirby, Deem, Larcombe-Weate, and Simpson work together, because if Carnal Vessels is anything to go by, we’re in for a treat for their oncoming filmographies.

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Kismet has brought audiences not one, not two, but three Aussie shark films. While I enjoyed Matthew Holmes’ Fear Below and Kiah Roche-Turner’s Beast of War, the sinister nature of Sean Byrne’s triumphant return to filmmaking, Dangerous Animals, is the one that stuck with me the most.

Firstly, a welcome constant with all three films is that the sharks that feature in them aren’t the villains of the piece. They’re simply creatures that exist in the orbit of the characters who find themselves in their territory. That’s a welcome shift away from the ‘killer shark’ trope that is so prevalent with shark films.

Secondly, what a delight it is to hear Jai Courtney in his Aussie accent again. I know it wasn’t long ago that we got his warm turn in Runt, but it’s even nicer to see him back again in an Aussie film that allows audiences to see that he can be a genuinely great actor when given the right material.

Thirdly, Sean Byrne is back to fight for the crown of being one of the best Aussie horror filmmakers around. Dangerous Animals is, for my money, the best Aussie horror flick of 2025. It’s nasty and gnarly in a way that makes you enchanted by the depravity of Courtney’s Bruce Tucker, while also wanting his victims to get away from his genuine deranged killing spree.

Just like The Loved Ones, Dangerous Animals balances pitch black comedy with tar like terror, swirling them together like chum in the water for us fucked up feral horror hounds to feast on. Byrne also continues his track record of changing the context of overly popular songs, with him doing for Pinkfong’s Baby Shark[4] what he did for Kasey Chambers Not Pretty Enough. I look forward to traumatising my nieces and nephews with this film when they’re old enough to watch it.

Listen to Nadine Whitney talk with Jai Courtney, Hassie Harrison, and Sean Byrne here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

It’s been heartwarming to see the outpour of love and passion for everybody’s favourite uncle John Clarke after they’ve watched Lorin Clarke’s glorious tribute to her father But Also John Clarke (or, for our New Zealand friends, Not Only Fred Dagg). Yet, it’s even more heartwarming to see people who either never engaged with or barely encountered John Clarke’s comedy voice a love and passion for the legend after watching the film. Such is the power of the legend that is John Clarke, a man who crafted a career of comedy and satire from the stage to screen.

But Also John Clarke is a gift from Lorin to audiences everywhere, with the storyteller opening over 200 boxes of archival material that includes John Clarke’s writing and letters and inviting those who miss his presence in our lives to remember why he was such an important figure in New Zealand and Australian culture. There are stories of fellow creatives like Sam Neill and Ben Elton who each talk about the role that John had on their lives, but there’s also stories about John being late for dinner because he generously spent time talking with strangers at the shops.

That level of generosity extends to Lorin’s filmmaking. Yes, she’s acting as a documentarian here, delivering a story about John Clarke’s life, a man who many of us felt like was a relative who we invited into our homes once a week alongside uncle Bryan Dawe, who would both tell us a few jokes about politics to make the week a bit lighter, but Lorin is also sharing a story about her father as his daughter. There’s a level of selflessness that comes with putting a film like But Also John Clarke into the world, a selflessness that takes an immense amount of courage and vulnerability. That selflessness also comes with a welcome dose of self-compassion for herself and for the audience who is missing someone like John in today’s political climate.

Satire helps us make sense of the world around us. It puts things in a line and says, ‘it’s ok to laugh at this, because sometimes laughter is all we have’. Satire also helps us remember that politicians and people in power are human too. We can laugh at their mistakes and failures, just like we’re still laughing at the Kirki tanker which caught fire on the morning of 21 July 1991 and then became immortalised in Australian comedy history when its front fell off.

What shifts a documentary like But Also John Clarke into its rarified space as a work of true brilliance is that it never feels like a clip show or ‘best of’ collection of John’s work. Instead, Lorin’s stories about growing up with John as a father are equally as funny and charming as the man himself. Because of Lorin’s proximity to John, the film becomes a tender invitation into the life of a legend. Laughing through tears never felt so good.

Listen to Lorin Clarke talk about the emotionality of But Also John Clarke here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

There’s a line early on in James Robert Woods’ Moonrise Over Knights Hill which speaks to why this slice of peak Australian comedy works so bloody well. The line, delivered by a character talking about reviewing submissions for the ABC, isn’t exactly funny or pointed, but it does speak to why Australian comedy is so dark and cuts through the bullshit so well:

"In our parole submissions, something we focus on is how we tell our stories."

The how of telling the story of Moonrise Over Knights Hill is why the comedy works so bloody well. First, there’s James Robert Woods’ script, which is full of delightful words like ‘charcutercuntery’ or conversations about the plight of Australian cinema – “What about Kenny? It’s actually pretty funny.” Then there’s the casting of Annelise Hall, Ben Gerrard, Josephine Starte, Luke Jacobz, Nicola Frew, David Quirk, Robert Preston, and Sapphire Blossom, all of whom feel like they’re playing characters who live and breathe outside of the frames of the film itself. What's even more impressive is the way that characters like the bloke who works in government funded arms dealing never become insufferable wankers. Somehow they're all endearing in their own fucked up way.

Then there’s James Robert Woods work behind the camera: on the one hand, his direction acts as a steadily controlled tiller, guiding the film through a heady mixture of biting comedy and social commentary, while on the other hand is his frenetic cinematography that captures the exploits like a documentary. Sure, his camera work might have had David Stratton running for the exit given how frenetic it is, but it does also manage to immerse you completely in the moment of three couples who take a trip to a retreat for a birthday weekend.

So it's the how of telling this story that makes Moonrise Over Knights Hill so bloody brilliant, making it a film that plays out like someone spiked the Goon of Fortune with acid and kept spinning the Hills Hoist til everyone had their fill. I watched this at home alone and laughed so hard that I even had to shush myself so I didn't miss another rip-roaring zinger of a line.

Like Carnal Vessels, Moonrise Over Knights Hill was given a stiff run on the festival circuit, desperately deserving a wider audience than what it received. When people bemoan the lack of good Aussie comedies, I’m stoked that I’ve got another two titles to point people to to prove them wrong. Just like Carnal Vessels, most of the people involved in this film are first timers or near enough, and all of them deserve long careers. I’m hoping that Moonrise Over Knights Hill gets a few more screenings in 2026, because I am itching to watch this with an audience of likeminded folks who need something to hoik popcorn out of our mouths as we struggle to contain our laughter.

Documentarian Yaara Bou Melhem returned to screens with her finest and most vital film yet, Yurlu | Country. Shot with deep reverence for the land it’s filmed on the subject it’s about by Tom Bannigan, Yurlu | Country follows Aboriginal Elder Maitland Parker, a Banjima Elder, over the last years of his life as he fights to restore his homeland of Wittenoom. Deemed ‘poison country’, this region of Western Australia has endured scarification and continued toxicity due to the asbestos mining that took place decades ago, and due to a lack of remediation from subsequent governments and the mining organisation that once mined the land, Maitland’s home is inhospitable.

Yaara’s considered documentation of the disconnect that exists between community, Country, and culture is presented with a level of anger and fury that never clouds the message of Maitland’s story and fight for restoration of the lands. The film also follows the medical process Maitland undergoes to treat the mesothelioma he was diagnosed with, caused by the exposure to asbestos fibres from the unrehabilitated land. Yurlu | Country is then a dual narrative of healing and sorrow, with the film becoming yet another entry in the library of documentaries which present how government after government after government continues to fail First Nations people, with profits for billionaires prioritised over maintaining continued connection to Country and culture.

Yet, with all of this written and all of this said, Yurlu | Country stands as being a towering work of cinematic and documentary filmmaking simply because it leans into the gentle nature of Maitland, allowing his story to guide the way that Yaara Bou Melhem, Tom Bannigan, and composer Helena Czajka, each become participants, and by virtue of his passing, custodians of sharing his story. Yes, this is a film that’s about a continued tragedy that lingers as an unaddressed issue by the government, and in some way it does become an awareness film (see the website YurluCountry.com for more information), but it’s about more than that. There is anger there, there is fury, but the key is to not let those emotions cloud your mind in the fight for justice and remediation of land.

Listen to Yaara Bou Melhem explore the creative process of making Yurlu | Country here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Australian prison films have become a genre unto themselves, and just like Songs Inside, Charles Williams’ Inside powerfully furthers Australia's cinematic relationship with incarceration. Here we meet Mel Blight (Vincent Miller), a youth-turned-adult prisoner who gets shifted from juvenile prison to become roommates with Australia’s most despised criminal, Mark Shepard (Cosmo Jarvis). On the fringes of that relationship is Warren Murfett (Guy Pearce), a soon to be paroled bloke who is shoulder deep in debt with fellow blokes inside and gets thrown a lifeline in the form of a payout for the offing of Shepard.

Shot with a cold yet earthly tone by Andrew Commis, Inside triumphs in the way that it makes us care about each of the three prisoners, pushing aside their crimes and asking us to see them as men simply trapped with one another. Vincent Miller echoes the work of James Frecheville in Animal Kingdom, a boy unsure how to become a man, conceived in prison and following his father’s footsteps as a crim who believes that this life is what he deserves, so he finds himself in a quietly spoken reality of eternal reckoning. Then there’s Guy Pearce giving a career best turn as a bloke who sees enough of the failed relationship he has with his son (a brief but sorrowfully impactful turn from Toby Wallace) in Mel to guide him into doing the deed of offing Shepard for them both to benefit.

But then there’s Cosmo Jarvis’ Shepard, a violent offender turned prison preacher who sees religion as a path to some kind of salvation, whether it’s for himself, or for the other prisoners, some of whom become beguiled by Shepard’s rambling in tongues, while others see him for the charlatan that he is.

There’s a pall of sadness within Inside, one that pushes the film apart from its genre siblings, most of whom are focused on delving into the crime side of prison life rather than the failed state of masculinity that is locked inside, waiting for a freedom that might never come. Those other films often invite us to take some kind of pleasure of excitement with the violence on display, or even to engage in a lurid admiration of the crimes of the prisoners; Inside defiantly asks its audience to see the prisoners as people. It questions the cyclical life of crime, poking at the almost genetic transference of criminality from parent to child and questioning whether it always has to be this way. In doing so, Williams then raises the notion of how social institutions can fail those they proclaim to support, forever playing catch up to stop more from falling into horrid cycles of recidivism.

The violence within Inside is horrific, and when it comes Williams presents it in a way that asks you, the viewer, whether you are ok with it occurring. In that moment, Williams shifts what an Australian prison film can be, questioning the way violence begets violence, a notion underpinned by Murfett’s offhand remark about how thin-skinned Australians are. Williams is saying ‘it doesn’t have to be this way, all of this, it can change’. And with that feeling, there’s a sense of mournful hope at the end of Inside, one that feels like after the endurance of shit, things can possibly get to a point of normal for Mel.

Read Nadine Whitney’s review of Inside here:

And her interview with director Charles Williams here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

Maybe the reason I didn’t sleep very well in 2025 was because I couldn’t shake the fever dream that was Adam C. Briggs & Sam Dixon’s A Grand Mockery. To quote Jacob Brinkworth, this is ‘genuinely DNA-altering shit for Australian cinema.’ This is a film that humbles you in its singularity. It’s the kind of film that should have aspiring Aussie filmmakers look at it and say, ‘wait, you can do that?’

A Grand Mockery was shot on Super 8 stock that feels infected with the ghosts of the cemetery that acted as a surrogate post office for Sam Dixon and Adam C. Briggs to share ideas about the film, literature, and anything in between. Dixon takes lead duties as Josie, a man inflicted with the reality of living in Brisbane. His girlfriend, of sorts, is Nelly (Kate Dillon), someone inflicted with the reality of living in Josie’s orbit. He’s not abusive, just someone stuck within the churn of casual labour and cinemagoers who see him as a vessel for delivering popcorn and that alone. It’s no wonder then that Josie finds comfort haunting the dead at the cemetery.

A Grand Mockery then devolves into a Lovecraftian influenced fever dream with Josie’s face becoming swaddled in bandages that barely manage to keep the oozing pus from pouring out of his neck. But maybe isn’t even a fever dream. Maybe it’s a form of reality, and it’s everyone else who is too stuck in a stupor to get out of it. If this sounds like it’s an unrelenting or nausea inducing film, then rest assured that A Grand Mockery carries one of the truest representations of bleak Queensland comedy around.

I want to briefly quote Shea Gallagher, of moviejuice lore, when talking about Adam C. Briggs’ work: “ACB is a chronicler and craftsman of things to be treasured. Crackling grain like crinkling parchment; bursts of light and blots of ink; friendship in lines. The flesh becomes word.”

Adam C. Briggs is quietly amassing a library of work that is, one film at a time, one postcard at a time, one letter at a time, shifting what Australian cinema and literature can be. His work thrives on the ephemeral; Briggs runs a letter club, of sorts, which I encourage you follow on his Instagram. Here, images flit into existence like entities appearing in the night, only to be gone by the time you search for them, their presence scorched into the lining of your eyes. Briggs also released in 2025, but I’m yet to watch, Boogie Bobby, and has also set free into the world the short film Write a Letter, and then, in 2021, Paris Funeral, 1972. I mention these films as a way of stating that if you happen to have a cinema near you that screens an Adam C. Briggs film, or even A Grand Mockery, then it’s your duty to watch these works in a cinema.

Memories of films get trapped in your mind in the darkness of a cinema. The haunting memory of A Grand Mockery has been one of the greatest gifts to receive in 2025.

While you can, Yellow Veil Pictures by way of Vinegar Syndrome have a bloody Bluray of A Grand Mockery for sale. Invite it into your collection here.

That David Robinson-Smith has gone and created a fairy tale of sorts with The Shirt Off Your Back. Maybe it’s less of a fairy tale and maybe it’s more of a fable or a myth that was created one Christmas Day sometime ago.

Two boys, Blye Hawk and Eden Wendt (credited as co-writers), encounter a man in a rusting yellow van on the fringes of a forest. He sits in the driver’s seat, leering from the shadow of the cab out of the passenger window at the boys. He has a simple request: he wants to buy Eden’s shirt for $20.

“How much for your jer-see? Twenty bucks is a very good deal.”

The Man is played by eleven different blokes, with Phoebe Taylor’s editing making the transition between akin to a horrifying kaleidoscope of lecherous beings, sitting in wait to snatch something precious.

Like all DRS films, The Shirt Off Your Back is a full-bodied experience, working as a whole to tension ball in your chest that threatens to burst with fury, but never does. Jaclyn Paterson’s haunting cinematography positions Blye and Eden at dusk, standing against the idea of a lake or with dull green mirage of foliage behind them. Wade Keighran's sound blends with his score collaboration Joel Byrne, layering the sound of the growl of the van over the chorus and cries of cockatoos and crickets. Fretting violins join in late as the presence of the sun is extinguished, and with it goes Blye and Eden’s innocence, alongside Eden’s jersey.

At the core of DRS work is the way yarning creates myths and legends. In those stories is the tinkering with memories and time, an instigating incident is an imperfect event that is bent and warped by our emotions. Mud Crab tells the creation story of toxicity and tension in a small community. We Used to Own Houses also plays with the idea of mournful memories, when the concept of owning a place you could exist in without concern has gone. The Shirt Off Your Back extends that exploration of myth making memories and the way time and emotions changes them, using Blye and Eden as vessels for the fracturing of innocence.

When I talk about the ‘rising swell of Australian cinema’, it’s filmmakers like David Robinson-Smith, Jaclyn Paterson, and Phoebe Taylor that I’m referring to. These storytellers are folks who are actively shifting what an Australian yarn looks like on screen. With the promise of a feature film on the horizon, the culture changing filmography of David Robinson-Smith is only just getting started.

Listen to this in-depth discussion with David Robinson-Smith about his filmography here:

Kaite Fitz’s Smoke stained my soul with its exploration of the hollowness of living in a stagnant relationship. For Lianne Mackessy’s Moira, living becomes something that happens to her as she wafts through existence, from yoga, to picking up takeaway, to waiting in the void of her home while her partner lingers in the ether of somewhere. Solitude is bliss they say – space around me where my soul can breathe – but that bliss is broken when he slinks into bed at night, the intrusion of his smell that he thought he managed to hide with a wave of his hand, smoke on his clothes, disrupting her existence.

Smoke is a tangible film, one that you can smell and taste, one that you can reach out and touch and feel. This is partly thanks to the cinematography from T. Oxford, someone who has presented a stunning sense of intimacy and a proximity to self throughout their work – see also Withered Blossoms (dir. Lionel Seah, 2024) and Bringing Home His Spirit (dir. Dylan Nicholls, 2024).

Smoke invites us into the increasing weight of Moira’s life, eking her comfortable solitude restoring art, to the failed relaxation of yoga, to the smothering of her blanket in bed. Fitz’s script and understated direction invites an understanding and acceptance of her solitary existence. It’s an invitation I kept responding to throughout the year, with Smoke become a touchstone of sorts that I would revisit throughout the year, as if it were a visualisation of how I have felt in the past that helped me make sense of a previous reality I’ve endured.

Watching Smoke, I got the same feeling I had when I stepped out of the cinema in 2017 watching Alena Lodkina’s Strange Colours, like I was witnessing the arrival of a singular talent that may come to define what gentle Australian filmmaking looks like. This encounter with Kaite Fitz’s work has become a revelation.

Listen to Kaite Fitz talk about Smoke and her drive as a filmmaker here:

In 2024 I was stunned by the work of Laneikka Denne in Sophie Serisier’s Oi. I’d drowned myself in their work that year, with Chris Elena’s sombre Passion Pop giving Laneikka the chance to play a ‘random lesbian’ – and doing an excellent job in the process, and Parish Malfitano’s utterly unique and almost indescribable Italian-immigrant witch-horror food-experience Salt Along the Tongue showing what Denne can do when given a lead role in a feature film. Sure, I rewatched Oi more than any other film in 2024, so much so that I crowned it the best film of the year – it’s really fucking great.

But so is Parish Malfitano’s second feature film.

Denne’s Mattia is a teen girl struggling to find her place in the world after enduring bullying at school, the pain of which is exacerbated when her mother unexpectedly dies. Mattia shifts into the home of her aunt Carol (Dina Panozzo), a woman who comes with a coven of exuberant women who work together on Carol’s cooking show. Parish embeds his Italian heritage into the text and tone of the film, exploring the Italian migrant experience in a way that few other films have done before. It’s a woman focused film – so much so that when a male character finally appears, you can’t help but shout in your mind ‘fuck off man’.

Like Smoke, Salt Along the Tongue is a tactile film. You can smell it, taste it, feel what its texture is like under you fingers – or even your fingernails. It’s alluring and enticing. It’s a little bit threatening and vicious, just as it’s a little bit viscous and festy. Like Malfitano’s debut film Bloodshot Heart, Salt Along the Tongue leans hard into vibes based filmmaking, letting the visuals and sound of the film conjure uncomfortable emotions inside you.

Salt Along the Tongue is shot and colour graded like no other Australian film I can remember. It’s got a bit of a sun kissed vibe to it at times, and others it feels like witches incepted themselves into a print of Looking for Alibrandi. Bowling balls look like gumballs and strawberries take on a deep crimson tone that looks inviting and threatening all once. The hazy half-awake look of the film is maybe the aspect that’s lingered the most in my mind – like I’ve dreamed the aftermath of a séance.

This is a film that I don’t think festivals or audiences entirely knew what to do with, and that’s a shame as it’s proof that Parish Malfitano is one of the finest voices this nation has given space to. Few filmmakers in Australia are telling generational stories about heritage, or intergenerational legacy, in the way that Parish is. It’s also a shame that, like Tim Carlier with Paco, Parish has shifted to London to find a space to spin his creativity. If only Australia understood the value of fostering and nurturing great talent like Malfitano and Parish while you have it, then we wouldn’t lose people overseas.

I’ll continue to be stunned by the work of Laneikka Denne and will always seek out a Parish Malfitano film, no matter where he’s making them from. The world is a better place with these two creatives in it.

For an in depth exploration on the visuals and colour grade for Salt Along the Tongue, read this piece by colourist Daniel Pardy on Digital Media World.

Listen to Parish Malfitano expand upon Salt Along the Tongue here:

Then there’s Lesbian Space Princess, a film which I had the privilege of experiencing my first Cannes-like standing ovation when it world premiered at the 2024 Adelaide Film Festival to a rapturous ten-minute applause. I think I can hear some people still clapping. I remember leaning over to Matthew Eeles from Cinema Australia and saying something along the lines of ‘that was fucking great’. He went on to say that this is ‘one of the greatest Australian films ever made’, and I’d have to agree.

Lesbian Space Princess is the collaborative work of geniuses writer-directors Emma Hough Hobbs, Leela Varghese, and producer Tom Phillips. It’s a bubble-gum splattered burst of neon brilliance that does exactly what it says on the tin: it’s queer as fuck, it’s set in space, and there’s a princess too. It’s the kind of film I didn’t know I needed until I watched it, and now I have it, I desperately want more.

There’s a fair few films on this list which I imagine will inspire future filmmakers to create imitations of them, or to say to themselves once more ‘I didn’t realise we could do that’, and Lesbian Space Princess is right up the top of that list. It’s Fun with a capital F. It’s unapologetic in how vibrantly queer it is (as if the title wasn’t a clear enough hint for you, this is the film that puts the L in LGBTIQA+). Emma Hough Hobbs and Leela Varghese’s script caters for a niche audience that is absolutely tuned into the Twilight references and the weird energy that comes with being the awkward person in a room full of sparkly, confident people. Or, to further quote Cody Allen’s review, ‘like the sparkly one who’s still just trying to keep it together’.

Lesbian Space Princess is as defiant a film debut as they come in Australia. It’s loud and proud and deserving of the praise and prestige that it’s been receiving over the past year, deservedly taking home the Teddy Award at the 2025 Berlinale Festival, and then going on to receive a swath of nominations at the 2026 AACTA Awards. But awards mean nothing if the film isn’t in service of the community it’s representing, and Lesbian Space Princess has done that in swathes. So, don’t take my word for it, take George’s review on Letterboxd, where they saw the film three out of the four times it screened in Adelaide in 2024, throwing five stars at it each time.

I absolutely adore Lesbian Space Princess. I live for its energy and its saccharine delight that kept me giddy for days after viewing it – and over a year on since that premiere, I’m still buzzing. Australian cinema kinda feels afraid of having fun some times, as if filmmakers need to embed some level of furrowed brow intent or a ‘message’ in the film to be taken seriously. Well, I hope after Lesbian Space Princess that notion is thrown out the fucking window, because gosh, we need this style of sparkle and joy in this film industry. This is an instant masterpiece of a film, the kind that I know I’ll be thinking about in decades to come and will be able to smile about when I do.

(Not included in this full list, but still worth shouting out for its brilliance is Leela Varghese’s short film I’m the Most Racist Person I Know which includes stellar performances from Shabana Azeez and Kavitha Anandasivam.)

Listen to co-directors Emma Hough Hobbs, Leela Varghese, and voice actor Shabana Azeez here:

Then listen to producer Tom Phillips here:

Then read the interview with Kween Kong (the voice of Blade) here:

And read Cody Allen’s review here:

Screening or Streaming Availability from JustWatch:

So then there’s Gabrielle Brady’s The Wolves Always Come at Night.